By Sunny Um WIRED Korea

Some call him a devil. Others say he is a criminal. He may find the condemnations too harsh. Still, what he did on YouTube cannot be easily condoned.

Three months ago, Hong Jung-oh, better known as “I’mTourette” on YouTube, tried to hold instant noodles with steel chopsticks in front of a rolling camera. Then he shook his head upwards and talked gibberish without warning.

Then he said to YouTube viewers, “You all should be thankful that you can eat food without (the kind of) difficulty that I have.”

Hong claimed to have Tourette syndrome, a disorder that is characterized by multiple motor tics and at least one vocal tic. It seemed his was marked by vocal noises and strange gestures made spontaneously. Hong said he found YouTube as an outlet to show his symptom and raise public awareness of the disorder.

Many were apparently intrigued by and sympathetic to Hong’s condition. Within a month, more than 300,000 YouTube users subscribed to his channel.

But on January 5, Hong’s former classmate said on an online community DC Inside that Hong did not have such syndrome in the old days. Some others raised suspicion about his tics, saying that he had released a rap album before his YouTube debut, which they said was not the kind of job a man subject to tics without warning could accomplish.

Hong uploaded a video for an apology the next day, claiming that he had exaggerated his disorder and admitting that he was a rapper.

Four days later, he changed the name of the channel name to “Zeneetou” and started to post his rap performance clips. Some YouTube users demanded that YouTube take action against Hong’s channel, claiming that he committed an act of crime when he deceived his viewers for profit.

Other accusations followed. One wrote in an online comment that he “is a devil that killed the handicapped with tics a second time.” Another said that he played with a disorder who affliction he could not hide from others though he wanted to. Also posted online was this comment: “Did you abandon humanity for money?”

Media Ethics of YouTube

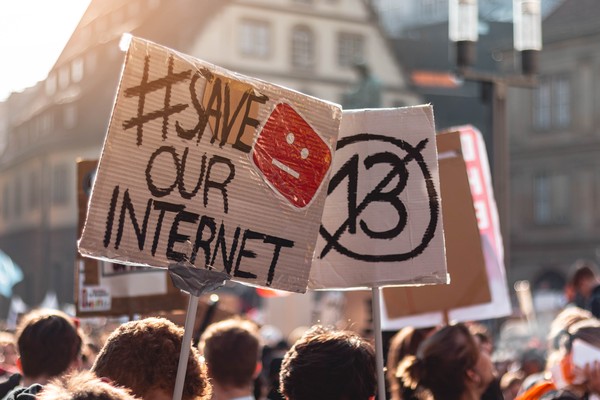

“I’mTourette” is just one of the innumerable cases of unfiltered abuse on Youtube. The problem with them is that there is little that can be done by Korean government regulators and civic groups advocating online decency.

True, YouTube staff regulate misleading or offensive clips and channels like Hong’s if community users raise a flag against them. The staff first review flagged contents and determine whether they violate the platform’s community guidelines – those that do not permit nudity or sexual act, hate crime, impersonation and many more.

The offending content may be removed based on the staff’s decisions, but the publisher’s channel can remain. YouTube may slap a one-time warning on a channel when it has no record of violating the guidelines. If the channel is found to have violated them again, it may order a temporary ban on the channel. If the channel owner gets two more strikes within 90 days, his channel can be removed.

YouTube measures are not proactive but passive. There is a considerable time lag between the posting of an inappropriate video on the platform and its removal from it. The reason is that YouTube acts against it only after it is reported by users.

Viewing all videos uploaded on the platform for regulation may be an impossible job for YouTube, which has a limited number of moderators. On average, clips uploaded on YouTube each minute has a combined running time of 300 hours. It should be a daunting task for YouTube to regulate an inappropriate video before it goes viral, even though its monitoring is assisted by artificial intelligence.

Another problem for YouTube is that what is offensive to some may not be perceived by others to be offensive, making it possible to subject a controversial clip to a subjective judgment by a YouTube moderator.

A case in point involves the former Vox host Carlos Maza, who tweeted that YouTube staffers didn’t try to stop hate speeches featured on the channel owned by popular right-wing pundit Steven Crowder. Crowder’s clips repeatedly made jokes about Maza’s sexual orientation and ethnicity.

At first, YouTube turned down Maza’s request to delete Crowder’s channel, saying it didn’t violate YouTube’s guidelines. But as Maza’s tweets gained more attention from the public, YouTube demonetized Crowder’s channel and said: “A pattern of egregious actions has harmed the broader community and is against our YouTube Partner Program policies”.

External Regulations?

It is highly unlikely that Hong’s channel could have made to the traditional media such as television and radio, which adheres to ethical standards under the Press Ethics Code. The Korea Press Foundation enrolls newly hired reporters and producers on its courses, including one on journalistic ethics, before they start work out in the field. In other words, journalists are called on to determine, based on the ethical standards, what content is appropriate for the public.

In addition, there is a layer of monitoring. The Korea Press Ethics Commission checks violators. Similarly, the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC) monitors broadcast programs and their outlets.

But the current Broadcasting Act does not regard internet broadcastings like YouTube clips as media contents. “Based on the current law, YouTube clips are not considered to be different from text posts on blogs,” says Kim Min-ji, a manager at Korea Communications Commission (KCC). “Social media platforms are categorized as common carriers, not broadcasters or journalistic outlets. The committees cannot regulate their contents as it does on broadcasting contents.”

KCSC may issue warnings against YouTube creators, but its regulations are limited to live streaming of hate speech, abusive language, and fake news. Moreover, the commission is not authorized to take action against YouTube content and channels.

“We can block responsible creators from going online in Korea. YouTube is a non-Korean business, so there is not much we could do,” says an official of KCSC.

Some politicians and others have attempted in vain to put YouTube clips under the regulation of media ethics committees.

For instance, Kim Sung-soo, a representative of the Democratic Party, submitted a revision bill of the Broadcasting Act to change to the National Assembly last June. No action has since been taken on the bill. There are few signs that it will pass the National Assembly any time soon, if it ever does.

Kim said: “This would provide a legal basis to regulate YouTubers under the Broadcasting Act.” The bill is still pending and unlikely to be discussed in the plenary session.

KCC launched the “Clean Internet Broadcasting Committee” with the participation of social media giants, such as Google, Naver and Kakao, in March 2018. But it dissolved itself the next year after proposing an ethics guideline that YouTubers could follow.

Experts say what type of regulations can be imposed on YouTube is still a matter of discussion. Kim from KCSC says, “Can people define live streaming as broadcasting? Should regulations be limited to online video content? We have much to debate before answering such questions.”

뉴스레터 신청

뉴스레터 신청